Get a masters in psychology to better understand the world around you.

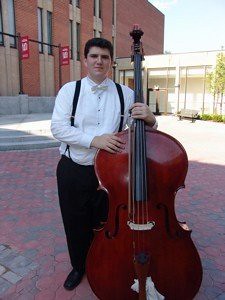

This is a post from double bassist from Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music student Nicholas Hart. Nick will be contributing weekly posts to the bass blog about life as a music student in one of the nation’s most exclusive programs. I think readers will find this different perspective on the double bass world and the music world in general to be quite interesting, and I am looking forward to reading these posts. You will be able to read all of Nick’s contributions under the articles link in the menubar or in the sidebar under contributors. Enjoy!

____________

Being in college when you are under 18 definitely has its disadvantages. For example, the University of Cincinnati is a very research oriented school and most classes have the students participate in mandatory research studies. However, students under age 18 are not legally allowed to participate and instead write a research paper. Normally I would complain about this but this time my Psychology professor assigned me a very broad topic and one I have enjoyed writing about – the psychology of being musical.

I came across an interesting article by Dr. Jay A. Seitz who is a professor of psychology at New School University and City University of New York. This article is based on the Dalcroze method and is titled “Dalcroze, the Body, Movement and Musicality.” The Dalcroze method is a fascinating pedagogical technique developed by Emile Jacques-Dalcroze and is based off of a simple principle:

“Rhythm is movement, movement is essentially physical, all movement requires space and time, physical experience forms musical consciousness, improvement of physical means results in clearness of perception, improvement of movements in time ensures the consciousness of musical rhythm, just as improvement of movements in space ensures consciousness of plastic rhythm”

Basically, Dalcroze argued that physical movement is the key component in musicality. Mr. Laszlo is known for two things, his advancements in the setup of the instrument, and movement while playing, or as he calls them gestures. Every movement we do when we play must have a purpose and, according to Dalcroze, movement creates our musicality.

“No physical movement has any expressive virtue in itself. Expression by gesture depends on a succession of movements and on a constant care for their harmonic, dynamic, and static rhythm. The static is the study of the law of balance proportion and the dynamic that of means of expression…Just as in music there are consonant and dissonant chords, so in mimic art we find consonant and dissonant gestures. ‘Consonant’ movements are produced by the perfect co-ordination between limbs, head, and torso, the fundamental agents of gesture. Exactly the same is the case when it is a question of harmonizing different motive elements of a crowd”

This statement by Dalcroze takes what Mr. Laszlo says one step further. Not only do the gestures create motion and energy to start phrases but they also are the major component to musicality – that musicality lies in our physical movements.

“The sensations afforded by the natural rhythms of our bodies strengthen our instinct for rhythm and create rhythmic consciousness. It is through this instinct and this consciousness, blended with aesthetic sense, that we experience complete artistic emotions”

____________

Dalcroze brings up very important points. All the essential elements of musicality – dynamics, tempi, articulations – are created by body movements. On top of that, the way we move and the way we “act” while playing portrays an emotion to the listener, and creates a form of visual musicality. An popular analogy of movement forming musicality is a conductor. The conductor is responsible for having 100+ musicians play musically the same way at the same time. The body of the conductor, along with the left hand, is used to portray emotions and entrances, big movements portray a loud dynamics while small a soft dynamic, horizontal motions draw a more legato sound and bouncy motions draw a more staccato and playful sound. All these movements are just examples of what we as instrumentalists can do to be more musical.

Along with movement, and maybe even more important is breathing. A major criticism of the Dalcroze Method is that it has very little to no mention of breathing, and does not focus on breathing towards musicality. In many of my lessons, Mr. Laszlo always talks about how breathing makes a phrase. If we seek to have a singing tone and lyricism like a singer, then should we not breathe like a singer?

Dalcroze talks about gesturing at the beginning of pieces, but by adding breathing to the gestures, this method can be taken one step further. When starting a solo, there should be energy and movement even before the first note to give the opening of the phrase direction. Mr. Laszlo often relates the opening gestures of a piece to taking a step. Before you take that step your foot must leave the ground and your body has forward motion and then your foot touches the ground once again and we repeat the gesture.

Before that first gesture, the rhythm of the piece should be internalized, then take in breathe, and release the breath and go through the gesture at the same time as the downbeat. This is similar in approach to how a conductor starts an orchestra during every piece.

___________

Our bodies must move in rhythm with the tempo that we are playing a piece. It is impossible for musicians to always play with a metronome, so we should train our bodies to become our metronomes. One way of doing this is bobbing your head slightly. Most teachers discourage tapping your foot as this can really cause some problems when playing in ensembles or when taking auditions.

Also, dynamics are created by breath and body. If we are thinking small, are slouched over, take short breaths, only using portions of the bow and are drawing the sound from small muscles, our sound will be small. The more movement we use the bigger our sound can be. This does not mean that we should jump up and down and do ridiculous things to create a sound, but it means we should think big, elongate our torso, take bigger breaths, and draw our sound from the big muscles groups that I previously talked about in my post on sound production.

To wrap up, musicality can be derived from our movement and bodily processes. Dynamics, melody, melodic contour, rhythm, emphasizing cadence points, accents, harmony and harmonic rhythm all can be drawn upon by our movements and breathing. I encourage all readers to explore all pedagogical methods of playing, the Dalcroze method is one of many methods, but the understanding of more than pedagogical technique is what makes truly great musicians.

__________

SOURCES

Seitz, Jay A – “Dalcrose, the Body, Movements, and Musicality”. Psychology of Music, Society for Education, Music, and Psychology Research. © 2005

__________________

About the Author

Admitted into the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music at age 16, Nicholas Hart is currently pursuing his Bachelor of Music degree as a scholarship student of Albert Laszlo. A product of the New York City Public School System, Nicholas attended the Juilliard School’s Pre-College Division where he studied with Eugene Levinson. Nicholas has performed in Solo, Orchestral, and Chamber ensembles throughout New York City in venues such as Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, and Symphony Space. Nicholas enjoys a long collaboration with the New York Pops, having performed with them and being one of the first recipients of their Martin J. Ormandy Memorial Scholarship. Additional studies include masterclasses with Harold Robinson, Timothy Cobb, David J. Grossman and Pasquale Delache-Feldman as well as summer study with Bret Simner. Nicholas has performed with such artists as Aaron Rosand and David Bilger, and aspires to play in a major symphony orchestra after college.

Related Posts from Nick:

- Contemporary Conservatory Life

- Mock Auditions

- Academic Loads

- Sound and Motion in Bass Playing

- Mental Aspects of Double Bass Playing

Bass News Right To Your Inbox!

Subscribe to get our weekly newsletter covering the double bass world.

Brilliant, Nick.

Keep ’em coming!

great post – as an ex-laszlo student – please please please don’t start playing with the brick!!! It’ll harm your chances in auditions – its very much mocked outside of CCM!!!

Take Laszlo’s technical ideas and the move on to someone else who has more of a realistic vision of things in the real world of bass.

Good Luck

Anynomous –

You’ll be happy to know none of us play with the brick anymore. He’s pretty much realized that it’s not accepted and we pretty much all play sitting.

Best,

Nick

Nick,

Great post! I really enjoyed this one and found it very abundant in great information! Great job.

I’m always glad to see mention of the Dalcroze Method! I just want to reply to one of your points:

“A major criticism of the Dalcroze Method is that it has very little to no mention of breathing, and does not focus on breathing towards musicality.”

In fact, Jaques-Dalcroze worked extensively with breathing. His method books are replete with exercises connecting the breath with music and movement in all sorts of ways. Different teachers focus on different aspects of the method according to their own experience and interests, of course, so it’s difficult to draw conclusions about the full span of his work from any one class.

Best wishes to you, and thanks for the opportunity to comment!

Monica

Hi, Monica:

You are absolutely right: If you read my original article I discuss Jaques-Dalcroze’s emphasis on the central importance of breathing.

Dr Jay Seitz