If you are interested in anything related to woodwind playing, string playing, phrasing, music education, orchestral performance, musicianship, the history of American orchestras, rhythm, sound, or the Curtis Institute, the name and teachings of Marcel Tabuteau are worth your attention. Marcel Tabuteau was one of the most influential figures in American music teaching from the 1920’s until his death in 1966. As one of the founding teachers at the Curtis Institute, he trained generations of leading musicians. He was an oboe virtuoso in his own right and played in many of the great American orchestras, finishing with 49 years in the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stokowski and Ormandy; however, he was not only hugely influential as an oboe teacher. He also taught classes in woodwind and string ensemble work that resulted in his impacting almost every student at Curtis. His ideas of how to approach phrasing and rhythmic groupings are legendary. I’ve always been very interested in how great teachers approach the challenge on transmitting purely musical concepts of phrasing and musicianship to their students, and Tabuteau’s ideas in this area have always piqued my interest.

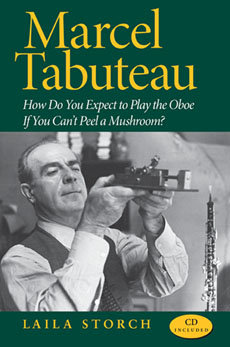

I was first made aware of Tabuteau years ago through a friend of mine who attended Curtis and was later was a graduate student at Peabody. She wrote her dissertation on Tabuteau’s influence on string players at Curtis and awakened an interest on my part in learning more about him. Unfortunately, at the time there wasn’t a whole lot of material available that provided any primary source information on Tabuteau. Now, that situation has been corrected, and in spectacular fashion. Laila Storch, one of Tabuteau’s only female students during his years at Curtis, has written a massive and surprisingly entertaining book examining Tabuteau’s life and career. An intriguing mix of scholarly research, extensive interviews with musicians and family members in the U.S. and France, and Storch’s own reminiscences and contacts with Tabuteau over many years, this book delivers a wealth of information on Tabuteau in a format that will intrigue both oboe scholars and musicians wanting to learn more about this amazing teacher and musician.

Storch covers the material relating to Tabuteau’s childhood in France, his training at the Paris Conservatoire, and his arrival in the US mostly as a historian and researcher, since there are few friends or colleagues still alive from that time to provide much eyewitness information. But as soon as he arrives in America in 1905, the scholarly tone of the opening chapters slowly begins to mix with interview fragments and reminiscences from former colleagues, students, and friends of Tabuteau. by the time you reach the years when Storch was a student of Tabuteau’s the book has transformed into a memoir, featuring reprints of the many years of (often hilarious) letters she wrote home to her parents while studying at Curtis. Then, as Storch graduates and moves on to professional oboe positions and a long teaching career, the book gradually morphs back into a primarily historical document. It’s a difficult format to pull off, and the personal memoir material could very easily have been a cloying distraction from the main topic of the novel. (I greatly disliked Martin Goldsmith’s book Inextinguishable Symphony for this very reason – his personal commentary on his parents’ lives and how they affected him always seemed to intrude into and interrupt the narrative of their experiences as Jewish musicians in Nazi Germany.) Storch manages to mostly succeed where Goldsmith failed, using her personal story and the reminiscences of others to provide insight and revealing anecdotes about Tabuteau, rather than turning the reader’s attention towards her.

In fact, Storch’s letters home from school are my favorite portion of the book. They provide a first-hand window into the intense, “old-school” teaching environment cultivated by the largely European Curtis faculty, and are also interesting reminders of life during the war years, when rationing and the draft colored everyone’s life (the only reason Storch was at Curtis was that there weren’t enough available men to recruit due to the draft – she was literally the Rosie the Riveter of oboe!). All the students at Curtis in these early years recall being in constant terror of displeasing their teachers, and it is made clear to all of them that they have essentially no rights or boundaries as regards the faculty – Tabuteau makes his students get his dry cleaning and pick up his groceries.

And they also provide a reminder that there was a time when Curtis was a brand new school struggling to establish its reputation, rather than the eminence grise it is today. Interestingly, much of Tabuteau’s teaching methodology came not from the great talent of the Curtis students he was working with, but rather from their often astonishing lack thereof! Tabuteau had to find a way to systematize the teaching of phrasing because there were so many Curtis students in need of his help.

The book is not specifically a textbook dedicated to explaining every detail of Tabuteau’s teaching techniques, although it describes many elements of them. The book does include a bonus CD featuring a recording of Tabuteau at the end of his life, playing orchestral excerpts and discussing his musical ideas; it’s very hard to discern what he’s saying on this recording, but Storch helpfully includes a transcript in the book.

I heartily recommend this book to anyone wanting to encounter and learn from one of the great pedagogues of all time.

Bass News Right To Your Inbox!

Subscribe to get our weekly newsletter covering the double bass world.

It was great to read about Laila Storch’s book on Tabuteau. As a student at Curtis I heard much about his wonderful playing and his numbered phrasing system. Everyone spoke of him with such reverence and affection. I will definitely get the book!

Incidentally, the bit in the review about Tabuteau making his students get his drycleaning and groceries made me laugh. I remember hearing about an incident that occurred before my time at Curtis when Roger Scott invited his students to his house and when they got there they discovered they were expected to paint his porch!

Thank you bringing this new book to my attention –

Great Roger Scott story – thanks for the kind words!

I read this book over the summer, and although we oboists revere Tabuteau as the “father” of American oboe style, I had no idea, until I did, how profound his influence was on musicians of all types. Any musician will enjoy this book, since Laila Storch did such a great job of integrating her experiences with him and making the story so interesting. What a golden age that must have been for musicians!