This is the third installment in a multi-part series on private music teaching. Check out part 1 and part 2 as well, and stay tuned for more installments in the near future.

Creating a Logical Curriculum

Though each student is unique and requires solo, étude, and technique selection tailored specifically to their needs, over time most private instrument teachers adopt some sort of multi-year lesson curriculum. This curriculum may adhere strictly to the Suzuki books, specific method or étude books. It may combine several disparate methods together. It may be based on tried-and-true repertoire progressions or may be almost entirely self-generated. It may be extremely regimented or quite loose. It may be heavily repertoire-based or exercise and étude-based. It may be slow-paced or fast-paced. It may be heavily based on rote learning or note reading.

Beyond the Written Curriculum

Of course, this dry listing of a progression of repertoire is only a surface look at a teacher’s true intent and philosophy. Why learn the Dragonetti so early? Why learn it at all?Where are the Simandl études?

More important, precisely what concepts and ideas are being introduced in each particular piece, scale, or étude? How are these concepts being presented? Why are they being taught at that exact moment in a student’s development?

Even more importantly, what happens when this rough curriculum progression doesn’t “take”? How is it adapted for students who need something else?

Finally, is this curriculum constantly being reevaluated by the teacher, growing and evolving as a teacher gains experience and sees the results of each step on students that have gone through the curriculum?

Given these considerations, it is impossible to nail down a specific “learn this, then this” curriculum template that works for every student, but I’ll give it a shot anyway. Here is my default list of pieces, etudes, and method books that, given no other information, I would work through with a student. This is certainly not the final word in bass teaching, but simply what I’ve come up with that works for me:

My Default Bass Student Curriculum:

George Vance Vol. 1

Simandl etude 1 (30 études)

George Vance Vol. 2

Marcello Sonata in E minor

Marcello Sonata in G major

Capuzzi Concerto (mvt 1-3)

George Vance Vol. 3 (work concurrently with Capuzzi)

Sturm Etudes

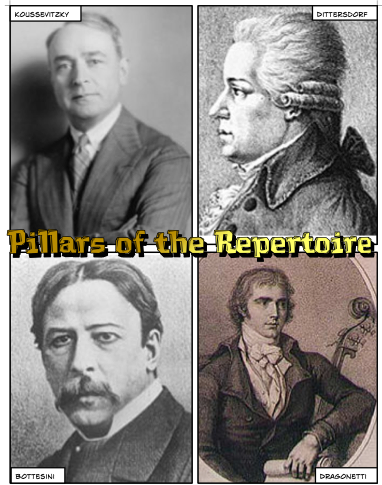

Dragonetti Concerto

Rabbath Ode D’Espagne

Sevcik Bowing Studies

Dittersdorf Concerto in E major

Eccles Sonata

Koussevitzky Concerto

Bach – selected movements from the cello suites

David Anderson Capriccio No. 2

Monti Czardas

Bottesini Concerto No. 2

Some Observations about this List

1. After the Bottesini Concerto, in my book, a whole world of repertoire opens up. If I work a student up to this point, the sky’s the limit.

2. I probably put the Eccles Sonata later in the list than others; I think that it is actually a fairly challenging piece for most student bass players, and while it is something that every bassist should learn, waiting until a certain level of technical proficiency is reached is a good idea. That way, the piece can be learned with more fluidity and with more confidence.

3. I like to throw in some less conventional solo pieces like the Rabbath Ode D’Espagne and the David Anderson Capriccio.

4. Some people may think that the Dragonetti Concerto comes a little earlier than expected in his list–look how far ahead I place Eccles, a piece that many learn before the Dragonetti Concerto. I use the Dragonetti as a “stepping stone” piece, one to teach upper register concepts, and I’ve got my whole schtick about thumb position, harmonics, and the like worked out for this piece, so it works well where t comes for my own style of teaching.

At what age should students reach these pieces?

I work with students of many different ages and ability levels, and therefore I may be working on the Capuzzi Concerto with a 6th grader and a senior in high school at the same time. It all depends on where they’re at on their own personal musical journey. Having said that, for students destined for a career as a professional bassist, these are fairly typical age concerto benchmarks:

- 8th grade – Capuzzi Concerto

- 9th-10th grade – Dragonetti Concerto

- 11th grade – Koussevitzky Concerto

- 12th grade – Bottesini Concerto

These are very general benchmarks and shouldn’t be discouraging to people who learned these pieces at an older age; I’ve had excellent students that haven’t learned the Dragonetti Concerto until their senior year of high school. Based on working with many students who went on to major music schools, these are vaguely where they ere in my repertoire list

Brainstorming Solutions through Repertoire

I firmly believe (and I’m not alone here) that students should be concurrently working on four major areas:

1. “Pure” technical exercises – scales, dexterity exercises for the left and right hands, shifting drills, etc.

2. Etudes – a combination of technique and repertoire

3. Solo repertoire

4. Orchestral repertoire (school music/ensemble music for younger students, and the standard orchestral repertoire for older students)

Do I cover these four areas in each lesson with students? Not necessarily–it all depends on what’s coming up for the student. If there’s an audition for an ensemble, we may go 100% orchestra repertoire for a few lessons; if there’s an impending recital, we’ll focus purely on solo repertoire for a period of time.

On Technical Exercises

I typically spend a few lessons from time to time focusing on pure technique exercises, trying to convey my own approach to doing this kind of work, and then I’ll eave the student to their own devices, checking in from time to time with the technique materials to make sure that they’re working on them consistently and in a logical fashion. I try to approach scales and exercises as calisthenics for the instrument, something do be done daily as a means to maintain and further improve the basic tools of the trade. I’ll get into this topic more in a future installment of this series–it warrants a post of its own!

On Etudes

I assign and check etudes weekly or bi-weekly, thinking them as applied technique exercises that can address certain weaknesses in a student’s playing or teach them overarching concepts about the instrument and about music. For a long time I didn’t use etudes; it wasn’t a big priority with any of my primary bass teachers, and I tend to (as most do) teach people the way I was taught. Over time, however, I’ve come to realize the value of assigning etudes. They’re a great way to teach concepts in a concrete fashion, and they are a nice tidy bundle of material that covers a specific issue in music or bass playing.

Final Thoughts

I hope that sharing this list of mine is of interest to folks out there, and I’d love to hear from other bassists what pieces they teach or what they learned as students, plus the order in which they learned them.

Bass News Right To Your Inbox!

Subscribe to get our weekly newsletter covering the double bass world.

Useful overview – thanks! I’m saving this one!

This is a great synopsis and reinforces various teaches notions of my own. Thanks for sharing. Agreed that Anderson / Capriccio No. 2 is a great addition to any teaching repertoire list. All the students of mine who’ve encountered this work love it and benefit from exploring it, with out a doubt.

Thanks again!

Correcting my typo:

This is a great synopsis and reinforces various teaching notions of my own. Thanks for sharing. Agreed that Anderson / Capriccio No. 2 is a great addition to any teaching repertoire list. All the students of mine who’ve encountered this work love it and benefit from exploring it, with out a doubt.

Thanks again!

Jason –

Thanks for posting this list. I am using it as a reference/reinforcement for the Wisconsin State Solo and Ensemble Bass Repertoire List. I especially like that you include the Rabbath and Anderson.