The following is a guest post from Double Bass Blog contributor Phillip W. Serna. Check out Phillip’s recitals and interviews on his Contrabass Conversations page, and visit him online at http://www.phillipwserna.com/. Enjoy!

__________________

Contrabass Conversations and the Double Bass Blog are continues is series on early bass performers. It will highlight many different perspectives on early bass/ violone performance. Our next guest is violone and viol performer and pedagogue Shanon Zusman. Professor Zusman has a lot of interesting concepts that are essential to understand how double bassists approach the earlier repertoire. We hope that you will enjoy these interviews and glean a good deal of information from our esteemed guests.

About Shanon Zusman:

Shanon Zusman is adjunct professor of violone and viola da gamba at the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music and Claremont Graduate University. He has also appeared as faculty at the Viola da Gamba Society of America Annual Conclave and has coached the Viols West branch of the society. He holds a D.M.A. in Early Music Performance from the USC Thornton School of Music, where he studied violone and viola da gamba with James Tyler. He has performed with Musica Angelica Baroque Orchestra, Camerata Pacifica Baroque, San Diego’s Bach Collegium, Los Angeles Bach Society, Los Angeles Baroque Orchestra, and Seattle’s Benevolent Order for Music of the Baroque. His research interests include the history of the double bass and its role in music of the sixteenth through eighteenth century, as well as other performance practice-related issues. Shanon can be reached by e-mail: szusman@usc.edu.

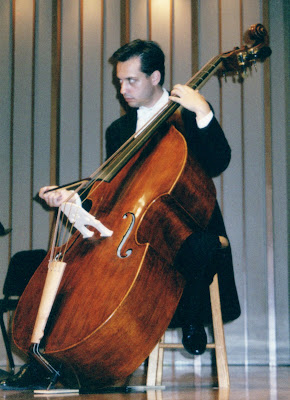

Shanon Zusman with Racz Viennese Violone

__________________

When and how did you become interested in early music, and how has it shaped your life musically?

I traveled to Europe in the fall of 1997 to study the history of the double bass, made possible by a grant from my alma mater, Loyola Marymount University. I had an opportunity to visit the musical instrument museums in Munich, Nuremburg, Berlin, and Vienna. This is when I became interested in the early history of the bass and got the bug to study early music performance. I received a Fulbright scholarship in 1998 and spent the year in Vienna studying the history of the bass in treatises, original parts, iconography, and early instruments at the Kunsthistorisches Museum and private collections. That’s when I met José Vázquez who has an amazing private collection of instruments which are regularly played upon by his conservatory students (http://www.orpheon.org/). José accepted me as a private student and introduced me to the viola da gamba family, including the violone in GG. I fell in love with early music that year abroad and decided to specialize in performance practice.

What instrument did you start on?

I actually started on the electric bass at the age of 10. I taught myself to read music and learned to play by ear. I picked up the double bass when I was 17 and studied with Jack Cousin of the Los Angeles Philharmonic as an undergraduate at Loyola Marymount University. I studied briefly with Donald Palma at the Yale School of Music in the spring of 1998. Then I went to Vienna (1998-1999) and took up the violone under José Vázquez’s tutelage. I transferred to the University of Southern California and continued my studies on violone and viola da gamba with James Tyler (graduated in 2002).

How has this informed your approach to period bass/violone performance?

My studies on electric bass and double bass have helped me to focus on sound production. You can get a myriad of colors on these instruments, and it has challenged me to approach period performance with an ear for different timbres. Also, learning to play “in the pocket” on electric bass has helped me to hear the violone as a rhythm instrument, to lay down a solid rhythmic foundation. The freedom to improvise in jazz and R&B genres has given me the confidence to shape or simplify a Baroque bassline, trusting my ears and musicality.

Who were some of the early music performers who have had a lasting affect on you?

I’ve been influenced and inspired by a number of early music performers. For his passionate approach and fearlessness in researching the history of the bass, Alfred Planyavsky. For their ability to combine research and performance, James Tyler and Peter Holman. For his amazing sound and bow technique, José Vázquez. For his musicianship and teaching methods, Brent Wissick. For his originality and creativity on the viola da gamba, Vittorio Ghielmi.

Where did you go to college for your undergrad degree? Master’s? Doctorate?

I finished a B.A. in Music and European Studies from Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles; started a master’s program in double bass at Yale School of Music, then spent one year at the University of Vienna on a Fulbright. After my “conversion” to early music, I decided to transfer to the University of Southern California. I completed an M.A. in Music History and D.M.A. in Early Music Performance at USC.

What would you recommend to college students looking to focus on early music?

Students should consider studying with a viola da gambist at a university where he/she can play in a Baroque orchestra and Renaissance consort on a weekly basis. There are several great programs out there (in America and Europe). I would recommend finding a program where the student might be eligible for a teaching assistantship through the music history department and/or scholarships for performing with the early music ensemble.

Did you do any summer festivals during your college years? If so, were these valuable experiences to you?

I attended the annual Conclave of the Viola da Gamba Society of America in July 1999. I played violone in GG for the week and the experience playing in small consorts was invaluable and addictive. That’s where I first tried the different sizes of the viola da gamba family (treble, tenor, and bass), and I think that helped me develop a better sense of rhythm, articulation, and timbre on violone. You really focus on listening to others when you play in a chamber ensemble, and one of my teachers, Brent Wissick, especially challenged me to internalize the pulse and open my ears. In 2001 I attended the Cambridge Early Music Summer School and studied with Peter Holman and Mark Caudle. Peter was an excellent role model as performer/scholar, and Mark challenged me to hear the melodic possibilities of a Baroque bassline.

What ensembles have you performed in (period instrument or otherwise)?

I have played with Musica Angelica, Bach Collegium, Camerata Pacifica Baroque, Los Angeles Baroque Orchestra, Los Angeles Bach Society, Benevolent Order for Music of the Baroque, and Concordia Clarimontis (faculty ensemble at Claremont Graduate University). I have also freelanced with a few ensembles on double bass and electric bass in Los Angeles.

What are among your favorite works to perform with these ensembles? Do any particular events stick out in your mind?

It’s hard to pick out favorite works as each concert is a fresh experience and chance to explore new repertoire. I always enjoy playing Handelian basslines, just about any Vivaldi concerto (lots you can do with rhythmic articulation), and cantatas by Bach (again, great basslines). I like it when I get a chance to switch between instruments in a concert. I’ve played Bach’s Johannes Passion a few times now, and it is always a challenging and emotional piece to do on violone (with the switch to gamba on the aria “Es ist vollbracht”).

Do you have any favorite performers you have worked with?

Rachel Podger as a guest soloist with Musica Angelica; Stanley Ritchie as a guest soloist with Los Angeles Baroque Orchestra; Ingrid Matthews with Los Angeles Bach Society.

What can we learn from studying early music?

Every sound you make is a statement of musical style. Articulation, phrasing, dynamics — these are left open to the performer in most early music repertoire, and it’s up to you to do something with the notes on the page. Playing in an early music ensemble is a more intimate experience, and as the only double bassist (usually), your voice stands out. So you have to decide what you want to say with every note, every beat. That’s of course the same in all good music-making, but in early music especially, the creative interpretation of the written note is integral to the performance.

What advice would you give to aspiring double bassists who might want to immerse themselves in early music?

Try to find a balance between playing and studying the sources/research. Read as much as you can on the history of the bass, both in original treatises and general early music studies. Listen to recordings by leading Baroque ensembles and soloists. Listen to solo recordings by viola da gambists and Baroque cellists. Try to develop your sonic imagination, and then experiment with gut strings on your bass. An instrument with gut strings cannot (and will not) sound like a modern double bass, so you should try to distance yourself from the sounds of a modern instrument. You have to be willing to check your expectations at the door and explore a new instrumental timbre and bowing technique.

What are the advantages of using period instruments?

You get to know a musical repertoire in a new way when you play it on a period instrument. I think it is more exciting to experience earlier music using the tools of the time. The double bass in particular sounds so different when you have frets on it. I find it easier to hear myself and others around me. That’s because the texture is more transparent with period instruments, and colors seem to “pop” more when you use gut strings.

Have you undertaken any research in regards to period instrument performance?

Yes, a lot of reading! There is a rich body of literature on period performance. And there are many articles and several books already written on the history of stringed instruments. Lately, I have been particularly interested in the early violone grosso (playing an octave below written pitch, as we do today) and its role in orchestras in the seventeenth and eighteenth century. When I am working on a project, I try to consult a number of different sources, including iconography (paintings), organology (instruments & bows), treatises, original parts (manuscripts and prints), and payment or scribal records.

What information would you impart regarding what kinds of instrument played at the bottom end in the 17th to 18th centuries?

Because there were so many variations of bass instruments in use, you should limit your research to a specific region within a specific time frame. For instance, the violone Monteverdi would have known is clearly not the same one Mozart would have used in his orchestra. No generalizations are really possible when you discuss the double bass in a historical context. You just have to take it case-by-case and accept that the “truth” is rarely black-and-white.

What sorts of materials (articles/treatises, etc.) would you suggest for an aspiring period instrument performer to understand performance practice issues regarding early bass instruments?

For performance practice, probably the most important secondary source to consult is Howard Mayer Brown’s Performance Practice: Music after 1600 (ed. Stanley Sadie, W.W. Norton, 1990). And most recently, John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw’s Birth of the Orchestra: History of an Institution, 1650-1815 (Oxford University Press, 2005). These studies will direct you to a plethora of primary sources (depending on which time/place interests you). It is also a good idea to have a look at Alfred Planyavsky’s Baroque Double Bass Violone (tr. James Barket, Scarecrow Press, 1998) and Ian Woodfield’s Early History of the Viol (Cambridge University Press, 1988). And there are two fabulous websites for learning more about the history of the double bass: Joëlle Morton’s http://www.greatbassviol.com/ and Jerry Fuller’s http://www.earlybass.com/. Both sites have several links to articles, iconography, and citations of important studies.

What, in your opinion, are among the most controversial issues regarding performance practice and bass instrument performance?

I think the most important question we have to ask with any given work composed before the 1780s is this: “What type (and how many) bass instruments should play the part labeled ‘basso’ or ‘violone’?” Does the repertoire call for a single instrument to read at pitch, or one at pitch with another an octave lower, or two instruments at pitch? Should the instrument(s) be members of the violin-family or the gamba-family, or both? What balance should we adopt (between instruments at pitch and one octave below)?

Another question directors and performers grapple with is: “When should you not double the bassline note-for-note?” It wasn’t really until Mozart’s time that we have an adequate number of parts written/published specifically for the double bass. So when a part is labeled “basso” we have to try out a few possibilities in instrumentation, but also in our interpretation. Two mid-eighteenth-century theorist-composers, Johann Joachim Quantz and Michel Corrette, describe the art of simplifying the basso part, and this practice should not be dismissed by period performers today.

One thing, however, to keep in mind as we ask these questions: it is usually wise to avoid the word “should,” whatever conclusions we may reach. We can attempt to address what was, what might have been, or what we ought to try nowadays. But when performers or scholars try to impose their findings, preaching as though there is only one “correct” way to do something, I feel they overlook the flexibility of the music-making process (as it was then and is now).

What aspects of period instrument performance do you feel that the majority of musical field are unaware of?

I think more attention should be paid to the various colors that are possible in an ensemble by tweaking the instrumentation and balance, especially in the basso continuo section. Directors should not be afraid to try a couple different arrangements. Lutes, organ, violone at pitch – we ought to try this more often (rather than the typical harpsichord, cello, and double bass combo). Also, for a great deal of seventeenth and early eighteenth-century music, perhaps we should try a viola da gamba on the part labeled “viola.” And one more idea: since we know that in some areas there appear to have been an equal number of violones and violoncellos in use (or even more violones), why not experiment with the bassline and try using the violone in new ways (rather than as a “double” bass all the time)?

What assumptions and misconceptions do period instrument performers need to present to future audiences?

I think we should be clear about the fact that when we perform early music and are trying to stay “true” to the composer’s intentions, we can never really remove ourselves from the performance. So while it is necessary to research and consult the origins of a work and performance practices, the final “product” is still a living artist’s interpretation, not a historical recreation or museum piece of sorts.

__________________

What kind of basses and violone do you play on?

My violone grosso is a copy of a Viennese bass attributed to Johann Georg Thir from the first quarter of the eighteenth century. It was built in 1999 by Barnabás Rácz from Gödöllö, Budapest. I have also frequently performed on a violone in GG owned by the Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California (when I was a graduate student and now faculty member). It is a copy of the “Dolmetsch” Maggini at the Horniman Museum in Haslemere made under the supervision of Roger Rose at the West Dean College in Chichester, England.

Do you play German bow, French bow? When you play violone, do you use a violone bow (large viola da gamba bow)?

My bow is based on an early Viennese bow with a German-style ebony frog. It is a fluted model made of snakewood by Louis Bégin from Quebec, Canada. When performing on a violone in GG, I prefer a very heavy viola da gamba bow and use gamba-style bowing (backwards from violin-style bowing).

What kind of strings do you use? What other brands have you used in the past?

Lately I’ve been using strings by Aquila. Mimmo Peruffo is an excellent maker and researcher of gut strings, and I’ve found his strings to be consistently good. I have also used Damian Dlugolecki’s strings. Damian is a great string maker, and there’s always a very fast turn-around time after placing an order. I like to use high-twist gut on my three highest strings and silver-wound gut for the lower ones (or high-twist on four highest strings when using a violone in GG).

Shanon Zusman with West Dean USC Maggini

__________________

For future installments in the Early Bass Performance – Early Music Interview Series, please visit the Double Bass Blog (http://www.doublebassblog.org/) and the Contrabass Conversations Podcast (http://www.contrabassconversations.com/).

subscribe to the blog – subscribe to the podcast

Bass News Right To Your Inbox!

Subscribe to get our weekly newsletter covering the double bass world.