This is a post from double bassist and music educator Peter Tambroni. Peter is currently a string teacher in suburban Chicago where he teaches string lessons in grades 3 – 8 and conduct the middle school concert and chamber orchestras. He also leads an Irish ensemble and a bass quartet. Learn more about Peter at his website petertambroni.com, and hear him perform and discuss the instrument on his Contrabass Conversations page. Read all doublebassblog.org contributions from Peter here.

__________

Zen, Mastery, and…Orchestra?!

Beyond practice charts, scales, and warm-ups. Alternative approaches for you and your students to reach your next level of mastery.

“There is no easy or difficult; only familiar and unfamiliar.”

– Kenny Werner, author of Effortless Mastery

What is Zen?

Zen is a way of life that fosters calmness, awareness and intuitive thinking. It enriches your life, encourages patience and is “a source of vitality and inner focus.” 1 It promotes natural and intuitive thinking.2 These characteristics are common among great teachers, performers, conductors, and all great musicians. However, there is nothing mystical or supernatural about Zen. It is something all of us can incorporate to create better classrooms, ensembles, and performances. The goal is to be in a state of mindfulness. Thich Nhat Hanh, in Zen Keys, writes “Mindfulness helps us focus our attention on and know what we are doing.” With a little practice both you and your students will be using another tool to assist them on their musical journey.

Being Mindful

We achieve mindfulness by being 100% focused on the present moment. Enjoying and being in the ‘right now’. And, well, right now is the only moment we can experience anyways so we may be in it all the way. This doesn’t mean ignoring facts or stimuli but rather let them be while you ‘be’.

For me, simply refocusing my brain and attention helps me to get into the zone. I ask myself some questions such as

1. What are your hands feeling?

2. Are my feet planted flat on the ground or am I tensing muscles and lifting my heels?

3. How is my breathing?

4. What are the sounds around me?

Now let’s put it into music.

Try this. Play a scale. Pick one you are very comfortable with. Rather than worrying about pitch, rhythm, tone, posture, etc., just be aware of your bow hand. Don’t nitpick, just feel. Feel the wood against your fingers. Notice the smooth ebony and octagonal pernambuco. Notice how it feel against your flesh. Now play with the scale with ultra long tones on each note — perhaps 5 – 10 seconds on each pitch. Take as many bows as you need on each pitch. Don’t worry about anything – just be aware of your bow hand. Be mindful.

You can try this again and focus on other parts – your fingertips, your back, your feet against the ground. You will probably find that other areas that you are not focusing on become more relaxed while your inner voice becomes less self-conscious.

The trick is always to slow down – both mentally and physically.Be deliberate but not forceful. But you have a recital coming up, right? All the more reason to relax. In my teaching I have found by teaching slower we are able to progress at a faster rate. It sounds contradictory but an analogy here works well. If we are in a car and race the engine the tires will not grasp the road. Even though the engine may be going at full speed the vehicle is not moving. But if we press the accelerator gently we will move forward as the tires gain traction. So it is with learning. Even the most advanced piece can by reduced to a chain of simple tasks that you are capable of.

The more you practice your instrument while being in a calm zone the more you will perform in that zone.

Slowing down – dispel the myth of 1 page per week.

“It doesn’t really pay to move on until something is mastered.” – Kenny Werner, author of Effortless Mastery.

Too many instrumental music teachers think they need to assign a new page every week. I don’t know where or when this idea originated but it seems to have always been there -when I was a student, when I was a student teacher, and now as a full time teacher. This often frustrates the young student who is already overwhelmed! Remember, this young person is thinking of many things – is my bow hand right? what did the teacher say again about my pinky? am I practicing enough? wait, how many fingers for a G? what position? did I use enough rosin? too much?

I will often assign a half of a page or even only a few songs. The students gain much more by being successful with less material that by struggling with more material. Assigning more material does not create better musicians, but mastering less music will always improve a musician. If a student is having difficulty with math, you don’t assign more problems you pick apart FEWER problems so the student learns the process and the inner workings. And do you as a teacher ever feel better by hearing more music that isn’t played correctly?

Rather than stepping on the gas pedal with the wheels slipping at 100mph, isn’t it better to do 10mph and actually move forward? Too many of us have spun our tires and pass on this useless high-speed method to our students. It is not a race to see who can finish Essential Elements first but rather to increase the level of playing with where the student is currently at.

Over the years I actually had to convince myself that it’s all right to give a half page, 1 example or 3 lines. IT IS OK! If the student can handle more, then by all means give them the challenge they need.

Teach thoroughly. The teacher sets the pace. The student does not. Just because the student wants to go on to the next page does not mean you should go along. I have found it useful to tell the students their book is designed to be a two (or three) year book. Most students think they need to get through an Essential Elements book in one year. That’s ludicrous and will only create a short-lived and shallow feeling of accomplishment. If they can’t play each page then what good is it to say they’re done?

The same concept of gradually moving forward rather than racing ahead can be applied, with great results, to the classroom or rehearsal setting. When you go slowly you will find something in your teaching and classroom that may have been missing – calmness. Feeling calm is positive and the effects on classroom atmosphere and student behavior are amazing. The students will sense a reduced feeling of pressure yet are very responsive since they are continually learning AND being successful. I am NOT implying that by covering less material the students are not learning or that the learning process slows down. On the contrary! By covering less material, you can go in greater depth and work the student’s brain harder! It sounds like a paradox but it works.

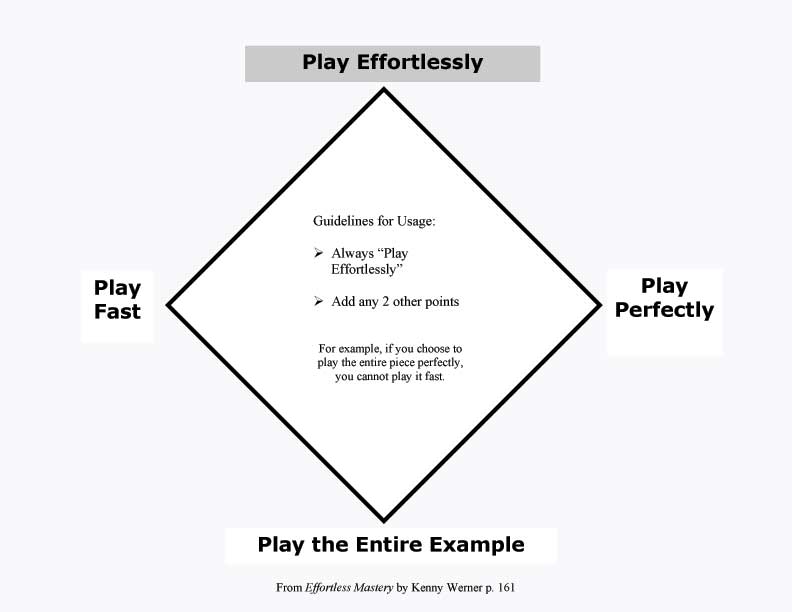

When teaching new music, use Kenny Werner’s “As slow as” rule. Play the music as slow as you need to go to play it perfectly. I also like to this diagram from his book. (try this link if the picture doesn’t show up well.)

What is our goal?

Educators want to do what’s best for their students. We think of different strategies to convey our ideas. We take classes to improve our craft. We arrive early and stay late. And, we give our students assignments to practice. All of this is in a quest to help students become better musicians.

As teachers, directors, and conductors, all of us plan for our lessons and rehearsals. Unfortunately, that planning is often geared toward the nearest concert looming on the school calendar. I view my teaching as long term, with a horizon of 5 – 10 years in mind. Is what I’m doing now with this student truly going to help them in 10 years whether they are a professional musician, amateur musician or audience member? Just as cramming for tests produces no long term benefits, viewing the concert as the be all end all of the students musical experience can provide no long term positive effects. I constantly remind myself to do no harm. Just as doctors are trained to first do no harm, so should we. Too many music teachers are ‘correcters’ rather than preventers. So many teachers don’t teach to prevent problems. They just correct them and this is very psychologically taxing because your are constantly dealing with negatives. How many times have you had to correct a students technique from a previous teacher? How many teachers will have to correct something you have taught (or inflicted on) a student?

Teachers do this to themselves as well with shoddy teaching at the beginning level. Go slow and teach correctly. This also ties in the 1 page a week notion. What a terrible thought. Do one line or even one note and play it perfect with perfect technique, posture, etc.

Prevent problems by teaching correctly and knowing what you want in the future from your students. If you want your 8th graders to know a chromatic scales your elementary students should know how to play a half step. And your beginners better know correct hand position to play the half steps in tune.

Unfortunately many music programs and curricula perpetuate this with busy concert schedules and performances. Obviously, concerts are an integral part of every music program. Students, parents, and administrators enjoy them and performing in public is an essential aspect of being a musician. I’m not saying to disregard their importance or preparation, but rather consider the concert as one component of a holistic music program, not as the only goal. It is always better to perform an easier piece well than a difficult piece poorly.

Teaching to the concert is stressful to both the teacher and students. If our only purpose is to please the audience then everyone is missing out on a truly musical experience. Suzuki students present a logical sequence of performances. At the very beginning a student’s recital may be just walking on stage and bowing in front of an audience. The student has mastered how to bow and show their appreciation to the audience. And when the time is right they want to show off their newly mastered skill. This creates a relaxed and enjoyable – albeit short – experience.

Where I teach, concerts are around an hour and oftentimes less. The parents have commented positively about the nice length of concerts and preparing one less concert piece allows me flexibility in the classroom to teach theory, improvisation and other aspects of music.

The Concept of Mastery

Most people have a false view of mastery. Mastery is not about being able to rip through all 24 of Paganini’s Caprices. Mastery is having effortless control over a note to convey your musical intentions to the audience. Can you, right now, play Twinkle in front of an audience with full relaxation and musicality? If not, some teacher has done you a disservice. Mastery is about having a relaxed flow to your playing, whether that’s an open D string or those arpeggios in Ein Heldenleben. It’s about being centered and grounded to the music and your instrument.

Sphere of Competence

The well-known investor Warren Buffet talks about staying within his sphere of competence. Dr. Stephen Covey, in his The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, writes about our sphere of concern. Your sphere of competence is the collection of skills and knowledge that you have complete control and mastery over at any particular moment.

How big is yours and your students sphere of mastery? Do your students even have one? I dare say that many of us don’t have one or have an extremely small sphere of mastery – because our sphere tries to encompass too much. Too many students have a sphere of mediocrity because their teachers are overloading them. The focus is on learning too much music or trying to finish their Kreutzer, Wohlfart, Schroeder, or Storch-Hrabe books rather than truly mastering one page. This is not say that you should limit yourself but rather not to sacrifice quality for quantity.

Many great solo artists have a very small repertoire list. They play a select number of – or even just one – concertos with many orchestras. They display their mastery of a given piece and transmit this beauty to the audience. Yes, some artists have a large list of sonatas they can perform but many travel and tour with a short list of pieces. This is what great people around us do everyday – SHOWCASE THEIR STRENGTHS. This is not gloating or showboating. This is an intelligent investment of personal energy and incorporates the Pareto Principal – that 20% of your effort causes 80% of your results. Therefore, by focusing the majority of personal resources on that which produces, gains are maximized.

The goal is to increase the sphere yet be brutally honest in evaluating where that current sphere truly is.

Mastery and Practice

Barry Green, author of The Mastery of Music, interviewed Edgar Meyer and asked him how he achieves his level of proficiency. The answer, of course, is slow practice. But Meyer takes it one level further and says when learning music he holds each note for eight seconds. Eight seconds! That’s discipline. I’ve tried this and have added it to my practice routine – especially when learning new music. There is something that happens when practicing that slowly – the notes get into your muscles and really become a part of you. This is similar to Suzuki’s method of making the music your own. It becomes second nature. Natural.

In my practicing and performing I have found that many problems are just me getting in my own way. When this happens I close my eyes and take a deep breath. I visualize the sound I want and see in my mind’s eye a great bass player performing what I’m working on. Let the musical passage tell you what it needs. We often try to tell the music or ourselves what the problem is, such as a left hand problems or bowing issues, when the problem is something else or something that we haven’t broken down or zeroed in on yet. Again, this sounds mystical but it is just allowing your mind to remain flexible, open, and aware of the entire stream of input coming to us – without passing judgment.

At the risk of perpetuating Harold Hill’s ‘think system’ it should be noted that visualization is an extremely powerful tool. In the book, Mental Toughness Training for Sports, author James E. Loehr, Ed.D writes visualization is “…a most fundamental and important exercise for every serious athlete.” 3

As musicians we are merely small muscle athletes and should use the tools that great athletes and Olympic champions use to achieve greatness. He goes on to say that visualization is “…a dramatically effective training technique for translating mental desires into physical performance.” 4

Letting Go…and Letting Go of Fear

Allowing yourself the freedom and abandon to play – to just play -, like a child completely absorbed into play is a powerful experience. Unfortunately, many of us have a difficult time recapturing that ‘moment’. Fear has inhibited too many of us. And that’s what it is – fear. We are afraid. Afraid of sounding bad, of being out of tune, of playing a wrong note, of somebody seeing us.

In reality, there is nothing to fear. Should you fear sounding bad? NO – It doesn’t matter. As Kenny Werner tells us, ‘FEAR NOT, THERE IS A GLUT OF GOOD…MUSICIANS!” 5

A listener can already go to a first rate concert or buy a phenomenal recording of any composition they want. It’s already there and already done ready to be listened to and consumed. So why learn an instrument at all and what are we afraid of? The purpose is to learn it for personal experience and ourselves. To move farther along the path and extend our journey on the plane of existence. If it is for ourself then there what is there to fear? The only thing we’re doing is cheating ourselves (both us and the students) out of a true musical experience. In the end, fear will only produce a smaller (if that’s possible) classical audience and people who resent quality music and music programs.

The first step to conquer fear is not to instill it in our students and orchestras. We need to pull them to higher levels; not push and squeeze the musicality out of them. When I was in graduate school at the University of Illinois, the orchestra conductor knew the difference between pulling and pushing. Rather than pushing the orchestra and applying negative pressure to obtain results, he always pulled and led us to new achievements. The level reached was much higher than could have been realized through mere pushing and squeezing. I had gone to grad school after a few years of teaching public school and was enthralled with his rehearsal technique. How did he do it? It wasn’t with the baton or fancy anecdotes displaying his obvious knowledge of music. He reached it through careful word choices, a subtle tone and voice and body language, and constant willingness to admit mistakes and look within to help the orchestra. Blame was never part of the equation.

Some teachers use fear to produce results. This is a quick fix and can produce quick – but fleeting – results. The long-term effects are extremely damaging. What happens to that student when he leaves your school at the end of the day? Or when he graduates? Do you think the fear that was put into him will make him enjoy his violin or truly love music? Will he, as an adult, become an avid classical music lover?

Greg Sarchet, of the Lyric Opera and Chicago area teacher, uses a slightly different means to eliminate fear. Our instrument is one of the few, and perhaps only (especially in a child’s life) aspect of our being that we can mold as we wish. ”I try to get students to feel safe with their instrument – to feel it’s an area of their life that they do have control – where there’s no or few other areas that you do have control. And there’s a great sense of liberation in that.” 6

That feeling of liberation not only frees you to make great music but lets the fear melt away.

Mastery, Quality, and Recruitment

Students are attracted to quality. By going slower and more thoroughly the quality of your program is sure to improve, thereby helping to retain and recruit students. Quality breeds quality and success breeds success.

These changes are not going to occur over night or even a year. That’s good! You don’t want a sudden change that’s going to disappear in a week. I’ve been at it several years now and I’m still working on it. You want these techniques to find a real home inside your teaching. Gradually incorporate some of these ideas over a few years and you’ll see both you and your students become masters.

The Zen of Nike

Just do it. What a great slogan. On the surface it may seem superficial but upon further examination this really is a prophetic statement. Just do it. Just practice. Just fix the problem. Just play. Just show up. Just. Just do it. In a recent lesson with a young viola player, the student was having difficulty playing a passage with a low first finger to get the needed A-flat on the G string. We picked apart the measure and played each note separately. We zeroed in on the note and examined our fingers and played some exercises to incorporate the A flat. But each time she played the music her finger kept creeping back up.

“It’s OK.” I said. This is a very bright student and this one note was getting the best of her. “Think for a moment. You know how to play the note and you know where to play the A flat. Picture your first finger playing the A flat. Tell it in your mind to just play A flat. I find saying it out loud help. First finger, play a low one at that spot. Just play it. Now visualize it. Go ahead and try it again.”

She played it correctly. By just telling her first finger to play the note her hand obeyed and played the measure correctly. Now, I am not implying for an instance that this is a substitute for diligent practice, scale work, and etudes. But when all else fails this method can be the right tool for the right job.

Tone of Voice and Classroom Demeanor

I’ve found that when I’m in the ‘Zen zone’ with my class some amazing things happen. I speak slowly and calmly. My interest and love of music shine. My students become really interested. And consistently, ANY AND ALL discipline or student interruptions cease.

To get students on that Zen path, try ‘clearing the air’ and centering yourself and the students. For example, in rehearsal when it’s time to move to the next piece, I put my head down and close my eyes, take a few deep breaths and after a few seconds look up and raise my baton to begin. What happens is, at first the group may be a little confused – they may not know if your upset or not, then things get quiet and a few students say ‘shhh’, and then a wonderful calm comes over the ensemble. It’s quite remarkable. Doing this consistently can really put your group into ‘rehearsal mode’ while maintaining calm and order. It is also quite effective in helping switch mental gears when the styles of different pieces are polarized.

Greg Sarchet of the Chicago Lyric Opera incorporates Zen and Eastern thinking into his own studio and teachings. “…aside from avoiding using loaded words that connote judgement, like ‘good’ or ‘bad’ or ‘should’, I prefer using “more”, “less”, or “some” in place of nebulous dynamic terms such as “p” or “mf” and the like. What occurs by using such words is the player (and listener) is drawn into the current moment, more focused on the present set of conditions.” 7

Modify Rather Than Judge

Do not judge – either yourself or the student. This is difficult to overcome! But by continually reinforcing ‘good’ and ‘bad’ or ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ you exponentially nurture the student’s self conscious and increase worry and ‘teacher pleasing’. We all know about wrong notes, rhythms, and ear splitting intonation. However, by changing the way we approach these we can foster a calm fix-it attitude rather than an “I’m horrible” attitude. Intonation is an aspect us musicians are constantly worrying about. But think about this, a piano’s notes are equal – equally out of tune that is! And the tuning A differs with each orchestra. A note’s ‘in-tuneness’ changes depending on the tonality and music. So, what is right? Is A always and forever 440? Of course not. So, then, what is right? The answer depends on the current situation. Therefore, there is no right or wrong, only a choice that works better for the current moment. That is a much more calming mood than, “you’re Eb is horrible!”

Mistakes are nothing more than feedback for continued growth. Without mistakes (perhaps there’s a better word…opportunities) the learning process would cease and our capabilities would stagnate.

Recommended Reading:

A Soprano on Her Head by Eloise Ristad

Simple Zen by C. Alexander Simpkins Ph.D. and Annellen Simpkins Ph.d

Energy Addict by Jon Gordon

Free Play by Stephen Nachmanovitch

The Inner Game of Music by Barry Green with W. Timoth Gallwey

The Mastery of Music by Barry Green

Effortless Mastery by Kenny Werner

Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff…and it’s all small stuff by Richard Carlson, PH.D.

Getting Things Done by David Allen

The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey

any writings by Thich Nhat Hanh

References

1 C. Alexander Simpkins, Ph.D. and Annellen Simpkins, Ph.D. Simple Zen, A Guide to Living Moment

by Moment. (Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 1999).

2 Ibid.

3 Loehr, James E., Ed.D. Mental Toughness Training for Sports. (New York: Plume, 1982).

4 Ibid.

5 Werner, Kenny. Effortless Mastery. (New Albany, IN: Jamey Aebersold Jazz, 1996).

6 Greg Sarchet of the Chicago Lyric Opera, interview by author, 12 December 2004, Chicago.

7 Greg Sarchet of the Chicago Lyric Opera, E-mail correspondence, 21 December 2004.

Bass News Right To Your Inbox!

Subscribe to get our weekly newsletter covering the double bass world.

I just read Effortless Mastery not too long ago. It’s good to see someone built a whole philosophy on it and other like books. Thanks for the post!

Thanks for taking the time to read it!

– Peter

THIS is the music ed philosophy that we so desperately need – thank you! not sure if you check for comments on these… but as a music ed student (in my last year) i’d highly enjoy a little email chat!

ps i’m a bass player too 🙂

pps – you should add ‘the perfect wrong note’ by william westney to that recommended list 🙂

wow! thanks for reading and commenting!

I will look into that book… in the meantime feel free to email me at tambroni AT hotmail DOT com