In The Rite of Spring, Stravinsky demonstrated an astonishing capacity for innovation, as an orchestrator as well as a composer. Examples of his prowess are too numerous to mention, so, in the spirit of not mentioning any, allow me to mention just one.

Top of page 2, the first time the bass section plays, holy shizz: six-part divisi? With harmonics?? IN TENOR CLEF??? Baller move, Igor. A well-blended bass section can make that chord sound as eerie as a sewer-dwelling clown.

Unfortunately, there’s one passage where he followed in the footsteps of many other composers before him: he wrote some seriously bass-unfriendly notes.

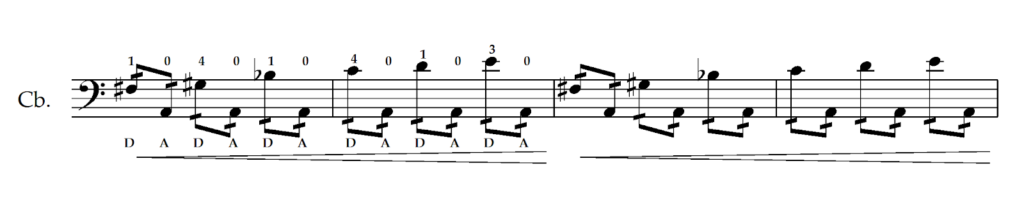

First of all, let’s look at some idiomatically solid bass writing, for the sake of contrast. At rehearsal 67 (“Cortege du Sage”), he has 3 basses play this figure:

But just a few measures later, just as Part I is wrapping up in a cacophonic frenzy, he writes something at 3 after 72 which strikes me as uncharacteristically un-idiomatic:

And a few measures later, it gets even un-idiomatic-er:

He’s obviously enjoying a little whole-tone scale fun at the bass section’s expense here, right? Unlike the passage at 67 (above), which alternates between fingered notes on the G and the open D, he seems to want the bass section to suffer, alternating between the D or G strings and the C on the A string. Why? Does he think we have a C string in that octave? Should we tune down our D? Or try playing the C’s as harmonics at the octave on the C string?

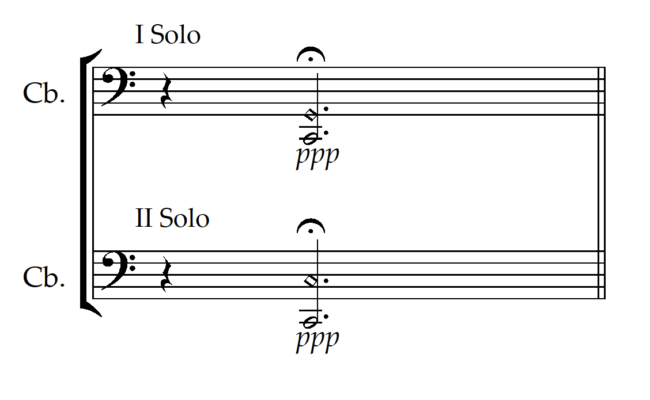

Let’s back up for a minute. Just before rehearsal 72, he writes these harmonics (natural harmonics, one assumes) for two solo basses, to be played on C strings:

So Stravinsky was aware that at least two of the basses would have C strings. But written in that octave, those harmonics are only playable as natural harmonics, not artificial ones, so it seems he expected C extensions instead of low B strings. Or B string tuned up a half-step? Someone nerdier than me should definitely answer that one.

To further muddle the issue, he gives the same music to the violas (who do have a C string available):

It seems like he was at least aware of, or even sensitive to, how much more playable the passage would be on an instrument with a C string. So why write the same notes for bass? Was the bass section of the Ballets Russes orchestra using a different tuning system? Someone reading this probably wrote their dissertation about that precise question; feel free to chime in.

The passage raises many questions but offers few answers. How can a self-respecting bass player get through this mess without resorting to faking it?

Hack it.

Make a C string. All it takes is a small piece of wood or plastic or stiff neoprene, wedged under your A string at the third fret (C natural).

Here’s a picture of mine, using a bit of rubber that a valiant and resourceful, if confused, stagehand found for me (white paper added for contrast):

The previously nasty-AF passage is now played thus, with all the open A’s sounding C:

And later:

This fingering even eliminates the need to cross to the G string in measures 2 & 4.

If you’d like to try this, but can’t find a valiant and resourceful stagehand to assist you, here are some other objects I found around my studio that might also work:

(clockwise from top left: bass wolf tone eliminator, ?” to ¼” audio adaptor, little pink pencil sharpener, fan pull that I accidentally stole from an AirBnB because I kept walking into it so I took it down and it probably fell into my luggage, harmonica, kazoo, tin of Altoids, flash drive containing mp3s of the first six Sigur Ros albums, vintage David Gage Bass Trunk key, a rock, a bass string winder, and a little tiny Snickers bar.) *Editor’s note: DO NOT attempt to use a little tiny Snickers bar, it WILL NOT WORK.

What would Stravinsky say, if he saw a bass section going to such lengths to stay true to his artistic vision by playing exactly what he wrote? I think, if he were alive today, he’d probably scream, “Laisse moi sortir! Je ne suis pas morte!” I think he would have more important things to worry about.

I don’t have more important things to worry about, I’m a bass player.

Bass News Right To Your Inbox!

Subscribe to get our weekly newsletter covering the double bass world.

My good friend introduced me to the idea of putting a rubber tourte mute under the A string for this passage. The Cs are a little diffuse but you can lean into the energy of the moment!

Frankly, I don’t see what the fuss is. The lick isn’t THAT difficult to warrant this “hack”. But that’s just my opinion. Not everything written for the bass is going to lie well on it. No other group of instrumentalists complains so much about these things. And that’s my DB rant/pet peeve for the day.

This is interesting. So, do these bars form part of a longer passage and if so, doesn’t the homemade capo get in the way of playing whichever other bits? Or do you have time to put the contraption on and take it off on the fly? And how do you test the pitch of your capoed C?

@Cesar: The passage is pretty isolated, there’s plenty of time before and after to make a quick alteration like this. And the C in question is audible just before the passage, as illustrated above (the “Solo II: harmonic.)

@Neil: kudos, you’re a better bass player than i am. I’ve performed Rite probably a dozen times, and i personally find this passage to be THAT difficult. otherwise there would be no hack. (of course, i[m what some call a “seasoned veteran”, meaning stuff that used to be easy now isn’t so easy anymore, tendons and muscles and flexibility and such, blah blah, uphill both ways in the snow, etc.)

I guess this “hack” is aimed at people like me. if you find the passage easy, my hat’s off to you. would love to see a video of you playing it.

@brent: Using a tourte mute is a great idea. thanks

It’s like a reverse capo???

But really, can never forgive Stravinsky (and Ravel) for introducing to the world the dreaded (and stupid) suono reali. All composers since them use their example and think it’s good because they did it.