It can smell fear. Like a vicious feral animal, orphaned early, neglected, and abandoned. It has a primitive, atavistic awareness of your weaknesses, it knows what time you take out the trash and knows what it will find when it tips the bins over. It knows how to survive in the post-apocalyptic doomscape of solo trombone literature.

It’s the TENOR CLEF! Run away, run away!

It’s here to make you feel illiterate, it’s here to confuse you and frustrate you and it’s…it’s…it’s GREEN!

Um, excuse me?

Yes, it’s GREEN. Tenor clef was designed for the conservation-minded: saving animals, trees, monks…

That probably deserves some explanation.

Ledger lines are expensive

Once upon a time, in the era when minstrels roamed the land begging for scraps of barbecued dragon from armor-clad knights named Percival or Aethelred, before Gutenberg (Steve?) brought fire from the gods and became the unofficial patron saint of monks with tendonitis, sheet music was painstakingly scribed by hand on parchment, otherwise known as vellum, which was made through a long, complicated, and malodorous process from animal skins.

The ink with which it was written was probably distilled from unicorn tears. Both were quite expensive, which is why most written music was church music, because the church had the resources that no one else did, because everyone else who once had the resources gave them to the church, because the church used to have pretty cool music, but then again, if no one else’s music got written down, then how would we know if other music was any good? Maybe some traveling minstrel was touring Wessex with a kickin’ twelve-piece band tearing the thatched roof off with some murderous Bardcore. We’ll never really know…

Anyway, these monk-scribes were a frugal bunch, not inclined to waste valuable vellum-space on notes above or below the staff, lest they be Inquisited or fed to dragons or whatever. Hence, CLEFS.

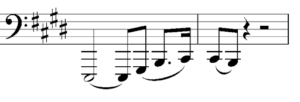

It’s why the double bass is technically a transposing instrument (this might be news to some of you). Yes, we read music printed an octave higher than it actually sounds. Imagine if we didn’t, and you showed up at your opera gig and opened your music to this:

So composers and editors threw us a bone, thus octave transposition, and bassists were rescued from ledger line purgatory. But that was then.

The Middle Path

And this is now: the bass has been liberated from being an orchestral afterthought and perennial punchline by virtuosic players and bold composers. We are now monarchs of all we survey, playing great music from any composer in any century, writing it for ourselves when inspired, stealing it shamelessly from other instruments when necessary.

The era of the double bass as a solo instrument has led, however, to a spot of bother among publishers and editors: should our music be printed in bass clef with too many leger lines, or with an intrusive and perhaps confusing “8va” bracket over the nasty bits, or should we constantly switch between the safe haven of bass clef and the exalted stratosphere of treble?

Or is there a middle path?

Consider this measure of Bach Cello Suite No. 1:

Easy to read, yes. But not accurately notated for bassists. So, either cluttered:

or:

But then eventually you arrive at:

or:

Which is fine, until you get to:

(This is starting to feel like one of those infomercials where otherwise healthy, competent people are unable to open a closet door or unscrew a lid without calamitous consequences.)

Cue the naysayers: “But reading the first suite cello music is actually pretty easy. Also, shut up, nerd.”

Okay, yes, and no, and then consider the fourth suite in D, as played, notated in bass clef:

Or notated more legibly, but in the wrong octave:

Tenor clef to the rescue!

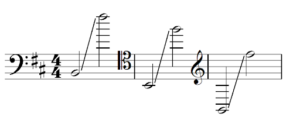

In the context of the Fourth Suite Prelude, notating the entire movement in tenor clef means no jumping between clefs, less visual clutter, and it might save a few monks from the rack. Behold the pitches at the low and high ends of the pitch range, or tessitura, of the fourth suite, in the different clefs:

Obviously, tenor expresses visually the tessitura of the piece better than bass or treble, But of course context is key: in many cases, I’d rather play it safe in bass clef; it’s the first clef I learned, it’s much cooler down there (hot air rises, remember), and everybody who lives down there is more laid-back and friendly.

But sometimes I don’t enjoy counting leger lines, or trying to remember which clef I’m dwelling in currently, or maybe most importantly, times when a student can’t figure out without a smart-phone app what pitch is right there on the page staring at them, times when the sophisticated bassist yearns for that middle path.

Ever Grope Bald Dudes?

“But learning to read and tenor clef is hard,” you say. Is there a reason why it should be any harder than learning to read bass or treble? Of course not. You learned those just fine.

Maybe you were helped by a mnemonic device, like “All Cows Eat Grass” or “Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge” (or “Does Fine”, but I prefer the fudge.) Okay, how about DFACE: “Dr. Freud Analyzed Cowardly Eggheads” or “Dog Finds All Cupboards Empty”? Or EGBD: “Everybody Gives Barbara Diseases” or “Ever Grope Bald Dudes?”

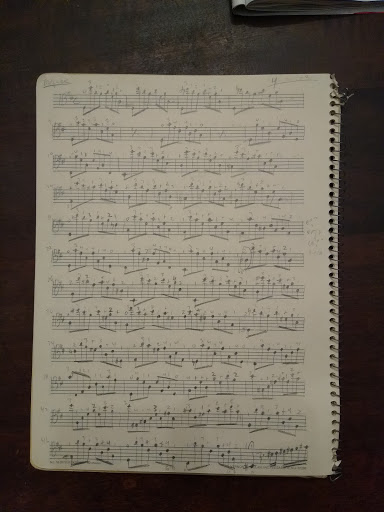

Or just take your medicine and learn the darn clef. I did, twenty years ago, learning the Fourth Suite in D. Here’s my ancient, pencil-scrawled manuscript of page 1:

Imagine learning this with a few dozen more ledger lines per measure. Sure, you could do it if the staves were farther apart, but fewer staves per page means more frequent and less convenient, page turns. And to me, there are few things in printed music more frustrating than inconvenient page turns. It’s like the editor telling us, “Turn early, or late, or whenever. Skip a note or a bar, no one will miss you. In fact, take the day off. And yeah, tomorrow too.” Well, the composer apparently thought it was worth it to include basses, so if you don’t mind, please PRINT ME LEGIBLE MUSIC!

So I stuck with it tenaciously, got used to it, began to recognize a few pitches at sight, and transpose the rest up a fifth from bass clef until I became fluent. Just another language, another system, another tool to use. Incidentally, “tenacious” and “tenor” come from the same Latin root word: tenere, meaning “to hold”. Not really pertinent, unless you consider tenacity a worthwhile trait for a practicing musician.

Really, tenor clef is a tool every advanced bassist should carry in their toolbox along with their steel wool and knowledge of obscure composers, a useful one for keeping printed music within a certain pitch range on the staff where it’s most easily parsed. And the more solo music modern bassists devour, the more publishers will find it economical and useful to utilise tenor clef. It keeps scores looking tidy. It boosts your self-esteem and your sex appeal. It slices, it dices, it changes your oil. And saves trees, and monks.

No ketchup-bottle-thumping subsonic frequencies, no nosebleed pyrotechnic high notes; those are already expressed capably by bass and treble clefs. But for that sweet, juicy, resonant, sexy middle range, give tenor clef a try. Let it prove its usefulness. Stick with it. At least it’s not alto clef.

Bass News Right To Your Inbox!

Subscribe to get our weekly newsletter covering the double bass world.

Michael, you make all great points and I totally get it. As a struggling late in life reader, I would actually prefer Alto Clef since, to me anyway, it is easier to visualize it superimposed an the Grand Staff smack in the middle. Comes in handy when playing the viola parts too. Although for the ultimate in notation for the challenged reader there was a piece I was trying to learn that I wrote out on computer using a Grand Staff and aside from wasted space it was lovely.